...

Humpback whales have a fluid social structure, often engaging behavioral practices in a pod, other times being solitary.

They are adaptable.

Distribution is worldwide: humpback whales are found in all major

oceans, including the Atlantic,

Pacific, and

Indian oceans,

including the cold waters of the Arctic.

Most rorquals are strictly oceanic: the humpback is an exception, which is oceanic but passes close to shore when

migrating.

Most rorquals breed in tropical waters during the winter, then migrate back to the polar feeding grounds rich in

plankton and

krill for the short polar summer.

SPLIT

PERSONALITY - This humpback whale skeleton reveals that the jaw is

in two pieces, with left and right bones hinged such as to be able to

spread wider when gulping vast volumes of water. The more seawater and

food that is ingested, the easier it is for these gentle giants to

survive.

EXTREME FEEDING

Humpbacks are one of the larger rorqual species, with adults ranging in length from 12–16 m (39–52 ft) and weighing around 25–30 metric tons (28–33 short tons). The humpback has a distinctive body shape, with long pectoral fins and a knobbly head. It is known for breaching and other distinctive surface behaviors, making it popular with whale watchers. Males produce a complex song lasting 10 to 20 minutes, which they repeat for hours at a time. All the males in a group will produce the same song, which is different each season. Its purpose is not clear, though it may help induce estrus in females.

Found in oceans and seas around the world, humpback whales typically migrate up to 25,000 km (16,000 mi) each year. They feed in polar waters, and migrate to tropical or subtropical waters to breed and give birth, fasting and living off their fat reserves. Their diet consists mostly of krill and small fish. Humpbacks have a diverse repertoire of feeding methods, including the bubble net technique.

Like other large whales, the humpback was a target for the whaling industry. The species was once hunted to the brink of

extinction; its population fell by an estimated 90% before a 1966 moratorium. While stocks have partially recovered to some 80,000 animals worldwide, entanglement in fishing gear, collisions with ships and noise pollution continue to affect the species.

BREATHING & (NOT) SLEEPING

Whales are air-breathing mammals who must surface to get the air they need. The stubby dorsal fin is visible soon after the blow (exhalation) when the whale surfaces, but disappears by the time the flukes emerge. Humpbacks have a 3 m (9.8 ft), heart-shaped bushy blow through the blowholes. They do not generally sleep at the surface, but they must continue to breathe. Possibly only half of their brain sleeps at one time, with one half managing the surface-blow-dive process without awakening the other half.

Due to the high metabolic rate, humpbacks need less sleep than other

mammals.

SINGING SONGS

Both male and female humpback whales vocalize, but only males produce the long, loud, complex "song" for which the species is famous. Each song consists of several sounds in a low register, varying in amplitude and frequency and typically lasting from 10 to 20

minutes. Individuals may sing continuously for more than 24 hours. Cetaceans have no vocal cords, instead, they produce sound via a larynx-like structure found in the throat, the mechanism of which has not been clearly identified. Whales do not have to exhale to produce sound.

Whales within a large area sing a single song. All North Atlantic humpbacks sing the same song, while those of the North Pacific sing a different song. Each population's song changes slowly over a period of years without repeating.

Scientists are unsure of the purpose of whale songs. Humpback whales make other sounds to communicate, such as grunts, groans, snorts and barks.

FEEDING

Humpbacks feed primarily in summer and live off fat reserves during winter. They feed only rarely and opportunistically in their wintering waters. The humpback is an energetic hunter, taking krill and small schooling fish such as juvenile Atlantic and Pacific salmon, herring, capelin and American sand lance, as well as Atlantic mackerel, pollock, haddock and Atlantic menhaden in the North Atlantic. They have been documented opportunistically feeding near fish hatcheries in Southeast Alaska, feasting on salmon fry released from the hatcheries. Krill and copepods are prey species in Australian and Antarctic waters. Humpbacks hunt by direct attack or by stunning prey by hitting the water with pectoral fins or flukes.

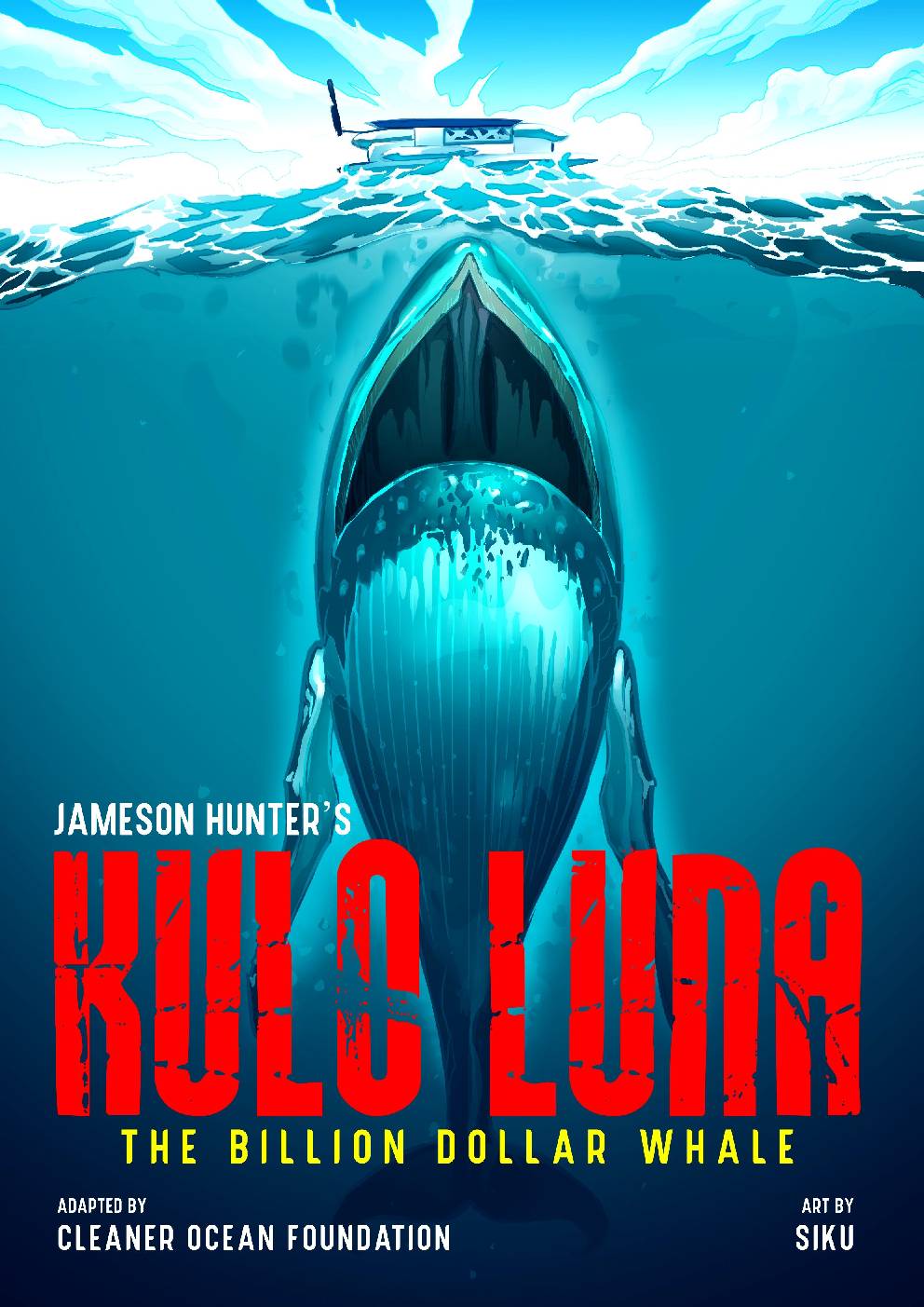

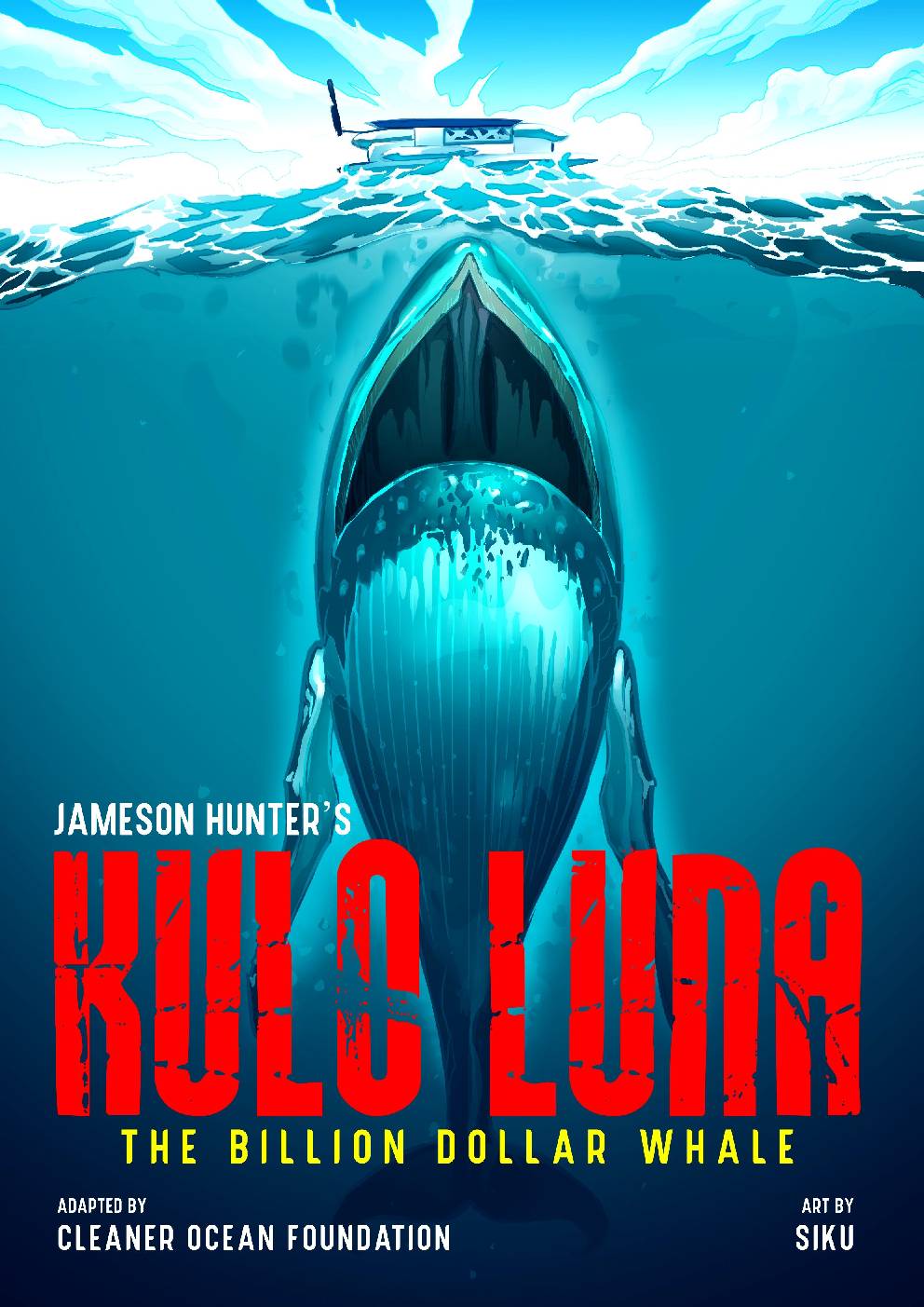

KULO

LUNA - In the genre of Moby

Dick, a humpback whale fights back against pirate whalers, sinking

their boat. This is the cover art for a graphic novel that the Cleaner

Ocean Foundation are hoping to produce as one of their ocean awareness initiatives.

Unlike Jaws,

baleens have no teeth, but she still manages one heck of a clash.

KILLER WHALES & SHARKS

Visible scars indicate that killer whales (orcas) can prey upon juvenile humpbacks, though until recently hunting had never been witnessed and attacks were assumed to be superficial in nature. However, a 2014 study off Western Australia observed that when available in large numbers, young humpbacks can be attacked and sometimes killed by orcas. Moreover, mothers and (possibly related) adults escort neonates to deter such predation. The suggestion is that when humpbacks suffered near-extinction during the whaling era, orcas turned to other prey, but are now resuming their former practice. There is also evidence that humpback whales will defend against or attack killer whales who are attacking either humpback calves or juveniles as well as members of other species.

The

great white shark is another confirmed predator of the humpback whale. In 2020, Marine biologists Dines and Gennari et al., published a documented incident they had recorded in 2019 in the journal "Marine and Freshwater Research" of a group of great white sharks exhibiting pack-like behavior to successfully attack and kill a live adult humpback whale. The sharks utilized the classic attack strategy they utilized on pinnipeds such as seals and sea lions when attacking the whale, even utilizing the bite-and-spit tactic they employ on said prey items. The incident is the first known documentation of great whites actively killing a large baleen whale and the first record known of a live humpback whale falling victim to this species of

shark.

A second incident regarding great white sharks killing humpback whales was documented off the coast of South Africa. The shark recorded instigating the attack was a female nicknamed "Helen". Working alone, the

shark attacked a 33 ft (10 m) emaciated and entangled humpback whale by attacking the whale's tail to cripple and bleed the whale before she managed to drown the whale by biting onto its head and pulling it underwater. The attack was witnessed via aerial drone by marine biologist Ryan Johnson, who said the attack went on for roughly 50 minutes before the shark successfully killed the whale. Johnson further suggested that the

shark may have strategized its attack in order to kill such a large animal, and may have had previous experience in attacking such large cetaceans.

MIGALOO THE EALBINO

Just as in Herman

Melville's 'Moby

Dick' an albino humpback whale that travels up and down the east coast of Australia became famous in local media because of its rare, all-white appearance. Migaloo is the only known Australian all-white specimen and is a true albino. First sighted in 1991, the whale was named for an indigenous Australian word for "white fella". To prevent sightseers approaching dangerously close, the Queensland government decreed a 500-m (1600-ft) exclusion zone around him.

WHALING

In 1946, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was founded to oversee the industry. They imposed hunting regulations and created hunting seasons. To prevent extinction, IWC banned commercial humpback whaling in 1966. By then, the global population had been reduced to around 5,000. The ban has remained in force since 1966.

Prior to commercial whaling, populations could have reached 125,000. North Pacific kills alone are estimated at

28,000. The Soviet Union deliberately under-recorded its catches; the Soviets reported catching 2,820 between 1947 and 1972, but the true number was over 48,000.

As of 2004, hunting was restricted to a few animals each year off the Caribbean island of Bequia in the nation of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. The take is not believed to threaten the local population. Japan had planned to kill 50 humpbacks in the 2007/08 season under its JARPA II research program. The announcement sparked global protests. After a visit to Tokyo by the IWC chair asking the Japanese for their co-operation in sorting out the differences between pro- and

anti-whaling nations on the commission, the Japanese whaling fleet agreed to take no humpback whales during the two years it would take to reach a formal agreement.

In 2010, the IWC authorized Greenland's native population to hunt a few humpback whales for the following three years.

In Japan, humpback, minkes, sperm and many other smaller Odontoceti, including critically endangered species such as North Pacific right, western gray and northern fin, have been targets of illegal captures. The hunts use harpoons for dolphin hunts or intentionally drive whales into nets, reporting them as cases of entanglement. Humpback meat can be found in markets. In one case, humpbacks of unknown quantities were illegally hunted in the Exclusive Economic Zones of anti-whaling nations such as off Mexico and South Africa.

Hunting

whales is forbidden by

international

law.

OTHER THREATS

Whales are vulnerable to collisions with ships, entanglement in fishing gear and noise pollution.

Like other cetaceans, humpbacks can be injured by excessive noise. In the 19th century, two humpback whales were found dead near sites of repeated oceanic sub-bottom blasting, with traumatic injuries and fractures in the ears.

Saxitoxin, a paralytic shellfish poisoning from contaminated mackerel, has been implicated in humpback whale deaths.

Whale researchers along the Atlantic Coast report that there have been more stranded whales with signs of vessel strikes and

fishing gear entanglement in recent years than ever before. The

NOAA recorded 88 stranded humpback whales between January 2016 and February 2019. This is more than double the number of whales stranded between 2013 and 2016. Because of the increase in stranded whales NOAA declared an unusual mortality event in April 2017. This declaration still stands. Virginia Beach aquarium's stranding response coordinator, Alexander Costidis says the conclusions are that the two causes of these unusual mortality events are vessel interactions and entanglements.

WHALE WATCHING

Whale watching is the leisure activity of observing humpbacks in the wild. Participants watch from shore or on touring boats. Humpbacks are generally curious about nearby objects. Some individuals, referred to as "friendlies", approach whale-watching boats closely, often staying under or near the boat for many minutes. Because humpbacks are typically easily approachable, curious, identifiable as individuals and display many behaviors, they have become the mainstay of whale tourism around the world. Hawaii has used the concept of "ecotourism" to benefit from the species without killing them. This business brings in revenue of $20 million per year for the state's economy.

..

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://

IWC is a voluntary

international organization and is not backed up by treaty, therefore,

the IWC has substantial practical limitations on its authority. First,

any member countries are free to simply leave the organization and

declare themselves not bound by it if they so wish. Second, any member

state may opt out of any specific IWC regulation by lodging a formal

objection to it within 90 days of the regulation coming into force (such

provisions are common in international agreements, on the logic that it

is preferable to have parties remain within the agreements than opt out

altogether). Third, the IWC has no ability to enforce any of its

decisions through penalty imposition.

Please use our

A-Z INDEX to

navigate this site